|

|

|

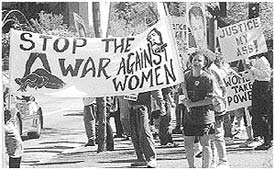

Violence

|

|

|

|

|

Putting the Liberation Back in the Women's Liberation MovementWith the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 (VAWA), domestic violence and sexual assault centers, police and district attorneys have experienced a huge infusion of federal monies intended to combat domestic violence - more than $100 million a year. In California and most other states, this windfall is controlled by the Office of Criminal Justice Planning (OCJP), a department of the State Attorney General's Office - that is, law enforcement. One of VAWA's novel (and naive) ideas was to make the money for domestic violence and sexual assault centers contingent on their forming partnerships with law enforcement. In our county, in order to get the OCJP funding - by far the majority of the centers' income - their grant proposals must be approved by every police chief in the county and the district attorney. Think about that: the cops now have total veto power over the money these centers depend on to survive. This has played out with predictable results. While the stated reasoning behind this was that cops would learn from advocates and become more sympathetic to DV and rape victims, that reasoning ignored the power imbalance inherent in these "partnerships." Rather than create kinder, gentler police forces who've been "educated" into enforcing the laws protecting victims, the result has been the complete evisceration of criminal justice advocacy for victims. What had once been grassroots, feminist institutions and activists fighting for women's right to be protected from male violence have become instead (willingly or unwillingly) well-paid handmaidens to the cops, doling out referrals and pats on the head at $150 a day. Criminal justice legal advocacy - getting cops, courts and district attorneys to enforce the law - has been almost universally abandoned. The effect on victims has been crushing. A case in point: when Purple Berets first formed in California in 1991, we did a lot of work in coalition with Sonoma County Women Against Rape, our local rape crisis center. WAR's victim advocate fought hard to get rape cases prosecuted and to make systemic change in police and DA practices and policies. Then in 1996, María Teresa Macias was murdered by her husband after being ignored by sheriff's deputies more than 25 times. It was Purple Berets and WAR working in tandem who investigated the case, organized and focused the public outrage, and ultimately won the landmark civil rights lawsuit holding the Sheriff's Department accountable for their utter refusal to protect Teresa. Targeted for Repression For Purple Berets, because we receive no government funding, their attacks were damaging but ultimately toothless. They simply didn't have the leverage to shut us up. But for Women Against Rape, they had all the leverage they needed - the purse strings. Over the next year or so, the WAR advocate who'd worked Macias was forced out, and WAR's county funding was ripped away. The battle then turned to their state OCJP funding. After more than a year of threats and finally putting the rape crisis center out for bid, an accommodation was made. What was left of Women Against Rape was forced to 1) change their name, removing the words "women" and "rape" from their handle; 2) agree not to take cases to the media; and 3) agree never, never, never to associate with the Purple Berets, among other things. This went so far as to have board members and volunteers sign a document swearing never to contact us - or even have coffee with us! The net effect: the institution (now named United Against Sexual Assault, or UASA) was saved, but victims lost everything. Not surprisingly, we haven't heard a peep of criticism of the police or DA out of them since. In fact, at their recent fundraising event, keynote speaker Sheriff Bill Cogbill's entire speech was devoted to recounting how they'd gotten rid of Women Against Rape. Far from hiding their naked manipulation of a once-feminist agency, the Sheriff's Department is bragging about it. Cogbill was followed by executive director Gloria Young, who also spoke about how much better things are now that they've destroyed Women Against Rape. It was shocking. Pay-Off or Pay-Back Not surprisingly, this became an object lesson for other rape crisis centers around the state. The resulting self-censorship and self-limitation has been nearly total. At the same time, all around California, rape crisis centers (historically by far the more feminist and radical wing of the violence against women movement) began to be swallowed up by the more pliant domestic violence programs. All in all, on a national scale, VAWA's $1 billion has bought silence with jobs. What were once firebrand activists are now police advocates pulling down $40,000 salaries, often making decisions based on job safety rather than victim safety. This is just wrong. As feminist lawyer Christine Pfau Laney said recently, "I just wonder what would have happened to the civil rights movement if, in 1959, the federal government had flooded their organizations with $1 billion. Do you really think desegregation would ever have happened?" The Voice in the

Wilderness So it was gratifying this spring to sit in a workshop at the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence conference called "The Problem with Programs: the Depoliticization of the Domestic Violence Movement." The room was filled to overflowing with activists and advocates, social workers and bureaucrats, all deeply disturbed by the constraints imposed on them by their budgets and boards. These were women who started out trying to change the world, only to find themselves expected to collaborate in women's victimization instead. One by one, they spoke of the effect of the "professionalization" of the movement, the removal of even the word "feminist" from their mission statements, and of being changed from "social warriors" to "social workers" in order to keep their jobs. Gone from their rhetoric was the language of patriarchy, of the institutionalized subjugation of women, of sexism, replaced by words like "syndrome" and "case management plan." These women were hungry for a movement; for women taking power, not bowing to it. They wanted to work for women's rights, not women's further oppression. Some Modest Proposals Clearly, though, there are a few steps that need to be taken now if the victims of rape and domestic violence are to have any hope for justice. Time to Get Off

the Tit But it won't take as much as you may think. The time spent writing those government grant proposals and the bean-counting and reporting required to keep them take a big bite out of the grants themselves. At the same time, centers are mandated by the grants to offer a lot of "feel-good" programs that could easily be eliminated without much effect on victims. Take the Cops Out

of the Funding Loop But there's a downside to that: whatever agency controls the funding, the movement will be warped to fit that agency's agenda. In those states where public health controls the funding, domestic violence suddenly becomes a "public health problem" rather than a hate crime. So even if we're successful in changing the face of "daddy" from cop to shrink, we need to see this as only a way station on the road to complete financial independence. Should the Shelter

Model Be Abandoned? Let's look at what happens when a woman goes into a shelter. Her kids are uprooted, often taken out of their schools. She loses her housing, which in today's economic climate will likely consign her to a couple of years of homelessness before she can get on her feet again. Often she also loses her job, either because her batterer knows where she works or because complying with all the shelter's "program" requirements leaves no time to go to work. And at many shelters a part of her meager welfare check (if she's lucky enough to still have one) is taken to pay "rent" on her room, leaving little for housing deposits and the other costs of creating a new life.

Plus, she's now doing childcare 24/7, watching her children like a hawk for fear she'll be kicked out of the shelter, or worse. And through it all, she's buried in rules and prohibitions, bullied by staff, cut off from her family and support system - in effect, she's in prison, while her batterer remains a free man. . . . Or Just Turned

on its Head? At least it would send the right message: rather than locking the women away so the police won't have to bother to protect them, we could lock the men away. Effective Law Enforcement

Is Key So if, instead of women's shelters, we put our time and resources into ensuring that domestic violence is prosecuted like any other violent crime, many of the problems victims face would disappear. The woman and her kids would stay at home, in school and in their jobs. She would be supported, rather than criminalized; empowered rather than imprisoned; liberated from the violence, rather than merely having her battering spouse replaced by a battering social worker. And most importantly, she'd be safe. Ask any woman at a domestic violence shelter if she feels safe. That's not to say that law enforcement alone can put an end to male violence against women. That will only come with feminist-based revolutionary change in the way our culture views women, views violence, views race, views safety. It's a long-term struggle, with no certainty of success at the end. But in the meantime, millions of women are being beaten and destroyed every year. The reality is that if we don't put the batterer in prison, we put the victim in prison - either leave her in the prison of the violent relationship, or put her in the prison and isolation of a shelter. Time for an Insurrection More women every year are beaten, held hostage, or killed by the men they live with or used to live with; those who dare to fight back are rotting in prisons. The costs to these women and to the society at-large are staggering. At this point, the only thing that has been proven to protect women is incarceration of the men who beat them. If there's a better solution, let's find it. If there's not, let's quit being afraid to demand that police do their jobs. It's time for us to get over our fear to even name the oppressor, and stop making (or tolerating) excuses for batterers and the cops who protect them. It's time to quit waiting for government funding to take care of women's rights (when has it ever?) and get back to taking care of them ourselves. That means increasing

our political and financial support for independent feminist organizing

tenfold - or a hundredfold - so we're free to set our own priorities

about what needs to be done. Anything less is deadly. July 2005 |

|

©

Tanya Brannan, Purple Berets

|

|

You

can copy and distribute this information at will

if you include credit and don't edit. |

|

|

|

Copyright

© 2001 Purple Berets

|

|

|

|

Web

Site by S.

Henry Wild

|